Access to Medicines Study

Study Profile

Access to Medicines Study

Aim:

The aim of this study is to improve equitable access to quality generic medicines for non-communicable diseases (Diabetes and Hypertension) in Tumkur district of Karnataka state in southern India. We seek to understand the health system factors that affect(either improve or hinder) utilisation and access to medicines for people with NCD.

Objectives:

• To understand if (and how) availability of drugs at government primary health centres (PHC) could be improved through formation of patient groups

• To understand if (and how) utilisation, compliance and quality of care for NCD at government primary health centres could be improved through training PHC staff and optimising existing service-delivery arrangements

• To estimate the additional costs for increasing rational use of medicines and services optimisation at PHCs

• To understand the health system factors that influence utilisation of drugs at government primary health centres

• To document the effects on the private sector of improved drug availability and utilisation in PHCs

India has the distinction of financing its healthcare mainly through out-of-pocket expenses by individual families contributing to catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment. Nearly 70% of the health expenditure is on medicines purchased at private pharmacies. Patients with chronic ailments are especially affected, as they often need lifelong medicines. Over the past years in India, there have been several efforts to improve drug availability at government primary health centres (PHC).

The access to medicine (ATM) study, being conducted by Institute of Public Health, Bengaluru aims to understand the health system factors that affect utilisation and access to generic medicines for people with non-communicable diseases. The study duration is of three years from 2013 to 2016. The study is implemented in three Talukas selected from Tumkur district of Karnataka. The study uses a mixed methods approach and involves a baseline and endline household (households having a diabetes or hypertension patient in it) and facility surveys. The qualitative component of the study involves Focus Group Discussions (FGD) and in depth interviews with providers and community members.

PHCs in the study taluks are randomly allocated to one of three arms of the intervention. In the first arm a package of interventions to optimise health services for NCD care are provided while in the second arm, an additional package of interventions to strengthen community participation platforms are being provided. The third arm is the control. Routinely all these PHCs were visited by our research officers for follow up to our intervention spanning across 18 months of time period.

The Aceess to Medicines study is a mixed methods study consisting of a quasi-experimental design for the quantitative component of the study and a qualitative component focusing on the conditions necessary for improving access to medicines in Tumkur district of Karnataka state in India(Fig 2). The study has been conducted at three talukas (Turvekere, Korategere and Sira) in this district. The quantitative component include a baseline survey and an endline survey of households, PHCs and private pharmacies which are planned before and after an intervention (Fig 1). There are two types of intervention, i.e. Health Service Optimization (training of PHC medical officers, pharmacists, ANMs on NCD care and management, Introduction of patient health records and awareness materials at PHC) and Community Platform Strengthening (ASHA training, mobilization of ARS fund for drug indenting, NCD patient group meeting and street plays). All (39) PHCs across these three talukas were randomly assigned to one of the three intervention arms of the study; intervention A, intervention B or control. In one arm, PHCs received inputs to optimise service delivery, while the second arm received an additional package of interventions at the community level. A third arm of PHCs will be the control. The qualitative component of the study includes in-depth interviews with key stakeholders and focus group discussions. This part of the study is using a theory-driven approach to understand and explain the changes if any, and why the intervention worked for some (where it did) and not for others (where it did not) across the three arms of the study. We also collected data on quality of medicines in PHCs and private pharmacies. We collected qualitative data from health workers and the NCD patients to understand the process as well as account for the possible diversity in the outcomes of the interventions across intervention arms.

(Fig 1) Study design of the ATM study

(Fig 2) Study sites

Duration of project

July 2013 – March 2016

Study activities

Baseline data collection

Data collection

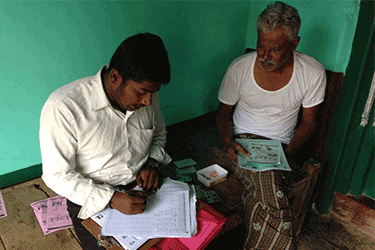

Data collection at the baseline phase (October 2013 to January 2014) included survey of households, Primary Health Centers(PHCs) and private pharmacies. Households in this survey included where atleast a patient suffering from diabetes and/or hypertension(NCD Patients) was living.It also included exit interviews with the patients suffering from diabetes and/or hypertension came to seek care at the PHCs. We also conducted qualitative focus group discussions (FGD) with NCD patients, community people and healthcare workers; while we also conducted in-depth interviews with PHCs medical officers, pharmacists and NCD patients.

Sampling strategy at the baseline phase

We conducted facility survey in all the 39 primary health centres and 30 private pharmacies near by these PHCs (roughly one private pharmacy nearby one PHC).

We conducted exit interview of patients (those suffering from diabetes and hypertension) to record their experience of the health care at the PHCs.We conducted around 10 exit interviews per PHC.

Map showing sampling of households and facilities

Intervention

The intervention was implemented in the three study sub-districts(taluks) spanning across a 18 months’ time period from May 2014 to September 2015. There are two types of intervention, i.e. Health Service Optimization (training of PHC medical officers, pharmacists, ANMs on NCD care and management, Introduction of patient health records and awareness materials at PHC) and Community Platform Strengthening (ASHA training, mobilization of ARS fund for drug indenting, NCD patient group meeting and street plays). All (39) PHCs across these three talukas were randomly assigned to one of the three intervention arms of the study; intervention A, intervention B or control. In one arm, PHCs received inputs to optimise service delivery, while the second arm received an additional package of interventions at the community level. A third arm of PHCs will be the control. The qualitative component of the study includes in-depth interviews with key stakeholders and focus group discussions. This part of the study is using a theory- driven approach to understand and explain the changes if any, and why the intervention worked for some (where it did) and not for others (where it did not) across the three arms of the study.

Step wise rolling of the intervention

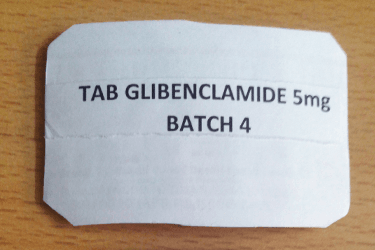

Drug Quality Test

A quality test for NCD medicine had been conducted as an independent activity of the study.

Endline datacollection

Sampling strategy at the Endline phase

For endline household survey we followed same sampling strategy with regards to cluster randomization. We adopted a panel survey of visiting to the same households as in baseline across 39 PHCs. In addition to this, we replaced new households (having a diabetes or hypetension patient)for those baseline households that we lost to follow up/trace (household could not be located, household locked, no one was in household to answer and household refused to respond) in the endline survey. In the endline survey we encountered death of the NCD patients in some of the existing baseline households. They were separately analysed and included in our sample size.

We conducted exit interview of patients (those suffering from diabetes and hypertension) to record their experience of the health care at the PHCs.We conducted around 10 exit interviews per PHC.

Trainings

Study outputs

Study Team

Funders

Collaborators

Capacity building - Team Members

- Attended two days seminar on Pharmaceutical Policies in India-Balancing Industrial and Public Health Interests at Delhi in July 2014.

- Attended a two day training on open source GPS mapping called “Mapping Essentials” in Bangalore in September 2014 organised by Gubbi Labs.

- Completed an online two month certification training course in Basics of Health Economics by World Bank from September to October 2015

- Completed an online two months certification training course in Fundamentals of Health Research Methodology offered jointly by Indian Council of Medical Research and National Institute of Epidemiology.

- Attended two days seminar on Pharmaceutical Policies in India-Balancing Industrial and Public Health Interests at Delhi in July 2014.

- Attended a three days training workshop on Research Methodology course with hands on training in SPSS at Bangalore in August 2014.

- Attended Good Health Research Practice training course Gadjah Mada University, Indonesia with support from WHO-TDR. Time- take from Website report.

- Attended and presented a poster- in Cape Town HSR Symposium 2014.

Blogs

What I learnt from my first health system research project

Dr Praveenkumar Aivalli blog titled, ” What I learnt from my first health system research project ” published in BioMed Central Starting my first research project Back in 2013, I just stepped out of my university after getting my Master of Public Health degree,...

How secure is India’s National Food Security Act? : by Manoj Kumar

Recently food security provisions in India has improved and not surprisingly the country is operating one of the largest food safety nets in the World. However regarding figures related to malnutrition particularly chronic malnutrition, the country is at very poor...

TB Stigma in India- a harsh reality even after five decades of a TB control Programme

In India, tuberculosis (TB) is still a major public health problem. In this blog, the author reflects on the stigma and discrimination faced by TB patients and how it affects their health seeking behaviour. Link to Munegowda CM blog in BMJ can be found...

Breastfeeding practices and child nutrition in India: By Manoj Kumar Patti

Many of us are aware that the importance of breastfeeding in child growth and nutrition.But have we ever wondered, in a developing country like India where many mothers are now into formal or informal work, why is it important to have a mother-friendly...

Road Traffic Injuries-An Ignored Public Health Issue in India

(Photo Credits- Biswarup Ganguly) The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1.24 million road traffic deaths occur every year globally. Of those, the majority (80%) of deaths occur only in middle income countries.Road traffic injuries are never considered a...

Tobacco control in India—more needs to be done to promote smoking cessation in India

This article originally appeared on BMJ Blogs on April 24, 2015 under the same title. Tobacco use is one of the single largest preventable causes of death and a leading risk factor for non-communicable diseases. The burden of tobacco related illnesses prompted the...

“Anything you get for free is not of good quality”: perceptions of generic medicines

This article originally appeared on BMJ Blogs on March 06, 2015 under the same title. The number of people with non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in India is increasing with each passing year. The World Health Organization estimates that NCDs could account for nearly...

Status of AYUSH doctors in the government healthcare delivery system in India

This article originally appeared on BMJ Blogs on February 26, 2015 under the same title. AYUSH—an acronym for Ayurveda, Yoga, Unani, Siddha, and Homeopathy—is a system of medicine that has been integrated into the Indian national healthcare delivery system to...