by iphindia | Sep 2, 2015 | Blog, ePHM-Advance, Latest Updates, Short Course

Introduction

Acute malnutrition or wasting is a failure to gain weight or actual weight loss caused by inadequate food intake, incorrect feeding practices, infections or a combination of these. Considered both a medical and social disorder, Severe Acute Malnutrition (SAM) is defined by very low weight for height (Z-score below -3 SD of the median WHO child growth standards), or a mid-upper arm circumference <115 mm/<11.5cm, or by the presence of bipedal nutritional edema.

Case fatality rate of SAM children with complications can be reduced by 90% through standard case management protocol like specialized treatment and prevention interventions at NRCs (Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres). Under national health programme in India, SAM cases are divided into two categories – those with medical complications such as diarrhea, fever, and pneumonia, needing facility based care and those without complications who can be managed in the community. Not more than 10% of SAM children require facility based care, after which follow up in the community is required to prevent relapse.

Nutritional Rehabilitation Centres in Odisha

Odisha is an underprivileged state in Eastern India and is categorized as an Empowered Action Group (EAG) state. It means it is among the nine states of India characterized with relatively higher fertility and mortality and accounts for 48% of the country’s population. Infant Mortality Rate of Odisha is 56 and Under 5 mortality rate stands at 75 (AHS 2012 – 13). Under-nutrition is the underlying cause in 55% of all the under 5 deaths. In Odisha, severe wasting among under 5 children is 5.2%, whereas in non-EAG states it ranges from 2 -4%. Scheduled caste and tribes comprise 40% of the state’s population who are socio economically the most challenged community. Various data sources like NFHS-31,AHS- 20132, Census 20113 and DLHS-34 show that Odisha still has high poverty levels, low female literacy, high incidence of malaria and diarrhea and poor IYCF practices. All these contribute to the poor nutritional status including SAM among under fives.

NRCs have been started under the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in Odisha and so far, 44 have been established with uniform bed strength of 10 per NRC. Currently around 75% of children are discharged as cured.

Challenges faced

Data from 16 NRCs of Western Odisha from July to December 2014 reveals several challenges faced by the NRCs

1. Poor bed occupancy rate (just over 50%) – this is due to poor detection of SAM in the field due to low levels of use of Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC tape) and poor detection of SAM with complications even at the Community Health Centers (CHC).

2. Few admissions of SAM children with complications (from case sheets maintained at the NRCs. Data on fever, diarrhea and ARI are not captured in the NRC MIS). SAM children with complications are admitted to the pediatric ward in larger hospitals and not to the NRC though there is a pediatrician in charge to manage such children.

3. High default rate (12.5%). Undernutrition being so prevalent in the community, it is considered normal and many mothers think it is un-necessary to admit children for being “thin”, especially when they fail to recognize symptoms of complications. Other responsibilities at home, loss of wages, cost of transport to and from the centre – all contribute to the default rate as well as to poor follow-up after discharge.

4. Poor follow up after discharge (less than 10% attend 3 follow up visits after discharge)

Therefore NRCs in Odisha mostly manage children who were low birth weight and fail to gain weight even after two months; mothers following poor IYCF practices; non-breastfed children and SAM children without complications referred by ICDS (Integrated Child Development Services) workers and supervisors.

The perception of severe under-nutrition as an abnormal condition can only be changed through intense nutrition education of the community, regular weighing of children and discussion of weights with the parents, and through proper counseling at the NRCs. NRC activities also needs to be more interactive and engage mothers. SAM children with complications mostly come from remote and vulnerable tribal pockets. Pressure for livelihood generation and household management do not allow mothers to get admitted in NRCs along with their children. Hence, wage loss compensation for mothers admitted in NRC should be increased to the current minimum wage, along with increased attention to improve nutritional status of tribal women through life cycle approach. Innovative strategies like working with self-help groups (SHGs), and the National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) groups can also be adopted.

NRCs will reduce child mortality but will not improve the general nutritional status of children in the community. Therefore preventive and promotive efforts must be continued.Strengthening of community based mechanisms for identification, prevention and management of severe acute malnutrition is a must, in the absence of which NRCs will not be effective. Facility based approach may prevent some under 5 deaths, but will not be useful in addressing this problem in the community

1 National Family Health Survey, 2005-06.

2 Annual Health Survey, Odisha 2013, Registrar General of India.

3 Census 2011, Registrar General of India

4 District Level Health Survey 3, Registrar General of India

Niranjan Bariyar was a student of e-learning course in Public Health Management(ePHM) conducted by Institute of Public Health, Bangalore, India.

Disclaimer: IPH blogs provide a platform for ePHM students to share their reflections on different public health topics. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and not necessarily represent the views of IPH.

by iphindia | Aug 21, 2015 | Blog, ePHM-Advance, Latest Updates, Short Course

India with a current population of 1.25 billion is posed to be the highest populated country with 1.6 billion by 2050. Indian public health planners have a huge challenge ahead – to serve and keep population healthy. Health care service resources will not increase in proportion to this population increase. The situation of high geographical disparities in health and wellbeing of population in addition to the demographic and epidemiological transitions taking place during this period will demand continuous spatiotemporal adjustments in plans and realignment of health care resources allocation. To address these challenges, health-planning process needs to evolve by provisioning maximum use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in health care delivery and public health decision making at every level. This is to deliver right health services to right people at right place and on right time.

India with a current population of 1.25 billion is posed to be the highest populated country with 1.6 billion by 2050. Indian public health planners have a huge challenge ahead – to serve and keep population healthy. Health care service resources will not increase in proportion to this population increase. The situation of high geographical disparities in health and wellbeing of population in addition to the demographic and epidemiological transitions taking place during this period will demand continuous spatiotemporal adjustments in plans and realignment of health care resources allocation. To address these challenges, health-planning process needs to evolve by provisioning maximum use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in health care delivery and public health decision making at every level. This is to deliver right health services to right people at right place and on right time.

Many academic literatures point to the importance of strategic partnerships between the ICT and healthcare sectors. To transform conventional information system into modern, real time and contextual public health information system, there is a need to strengthen health care data/ information collection, exchange and analysis using range of following available ICT areas: application service provision, database and software support, electronic health records, health information systems, intelligence systems, Geographic information systems, security services and tele-health systems.

Despite having a big ICT talent pool, infrastructure and other resources advantage, use of ICT in health care in India has not been successful and varies state to state. Low use of ICT in health care contributes to poor patient care, poor and slow data reporting to HMIS lead to delayed, inefficient and insufficient public health response. In a BMJ blog the authors documented their experience with vital registration system in Karnataka state in India. Though Karnataka has 90% vital registration recording, full potential of such data for public health decision and policy making remains unachieved. It is a general perception among health system researchers in India that private and unorganized health care sectors possess biggest challenge in successful use of ICT in health care. Many success stories both at international level and within India show that improvement in health care delivery owing to successful use of ICT. It boosts the utilization of state run health services; encourages private sector to join ICT wagon and will minimize or gradually eliminate unorganized and uncertified health care sector. In Tamil Nadu, HMS was launched in May 2005 that contributed to improved health care and allowed health workers, even in remote areas, immediately report disease incidence data to health officials. In turn, health managers were able to quickly analyze information about suspected cases, share technical information and resources, and initiate an informed response.

A careful and systematic review of documentation of various health care information systems around the world provides insight into factors contributing to the ineffective ICT and HMIS implementation. These factors include failure to take into account the social and professional cultures of healthcare organizations; inadequate attention to the need for education of users; underestimation of the complexity of routine clinical and managerial processes by IT developers; lack of commitment among stakeholders due to different expectations; not learning from past project failures; low understanding of ICT for patient care and in clinical setting by clinicians and health care practitioners and similarly missing health care context knowledge among IT professionals and data analysts; and not linking various health care and demographic information systems.

To reap the benefits of ICT in health care and public health, some fundamental measures are required to create ICT awareness and data culture among health care provider and public health decision maker. Measures as simple as introduction of curriculum on best use of ICT in medical courses can have huge influence on aspiring clinicians and health workers to record, organize, use and share patient information. Other successful measures being used around the world include developing a dedicated cadre of public health data scientist (Computer science + Statistics + Epidemiology + Public health + medical knowledge) – to collect, analyse, synthesize and transform public health data into intelligence to support timely evidence-based decision making at every level; establishing a national level health intelligence unit which collect information in real time from different sources; expanding and including the use of Geographical Information system to create public health geo-intelligence for rapid detection of health event of major concern ; improving health risk communication to public using various m-health initiatives; and integrating various health information system including census and vital registration system.

In conclusion I would like to say, careful, smart and contextual integration of ICT in health care service delivery and resulting improved HMIS should be core and prioritized strategies to response complex health need of a country of over billion people with diversified social and cultural practices. India needs to do it and do it now.

Ajay Goel was a student of e-learning course in Public Health Management(ePHM) conducted by Institute of Public Health, Bangalore, India.

Disclaimer: IPH blogs provide a platform for ePHM students to share their reflections on different public health topics. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and not necessarily represent the views of IPH.

by iphindia | Aug 21, 2015 | Blog, ePHM-Advance, Latest Updates, Short Course

The term Medical Devices, as defined in the Food and Drugs Act, covers a wide range of health or medical instruments used in the treatment, mitigation, diagnosis or prevention of a disease or abnormal physical condition. Medical devices are useful for easy diagnostics and effective instruments acting as a catalyst for treatment of many diseases.

Nowadays, rural medical devices are a boost to develop and developing countries around the world. CAMTECH, USA and Harvard Medical School are two examples who provide platform for many students to develop medical devices. CAMTech’s mission is to accelerate medical technology innovation to improve health outcomes in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). The CAMTech India Jugaad-a-thin brings together some of the world’s brightest minds to develop innovative health technologies.

In India, Moreover, NGO’s like SEWA Rural (Gujarat) are extensively working on mobile healthcare through SMS system and smart phones. Nowadays, many mobile sensor based healthcare I-Phone and android applications have come up which can detect the pulse heart rate etc. Diabetes, Alzheimer’s management apps have recently come up in play store. Students of Faridabad-based Manav Rachna College of Engineering have built an automated portable digital device which collects blood and urine samples to detect diseases like diabetes, anaemia and jaundice. Similarly, Hyderabad-based 20-year-old Asar Dhandala has developed Just Born, a Windows app that highlights the issue of female foeticide in India through a game. Similarly, a few IIT-Madras students managed to develop an automated screening tool to detect diabetic retinopathy. The software analyses the image of fundus (interior eye portion) and identifies the regions affected by the disease. Fractal has also developed Virtual Brailler, a device for the visually impaired that converts text to braille. The low-cost revolutionary product proved to be accessible to several millions who earlier depended on the tangible braille books or resorted to text-to-speech methods.

Mobile phone based Glucometers have now come into the market which helps the patient to check the level of glucose on cell phones and send the results to doctors directly. Public Health Foundation of India, Affordable Health Technologies division has designed Swasthya Slate, a system that allows an Android tablet/phone to deliver 33 medical diagnostics using a single kit. It has been validated in field tests in Punjab and Andhra Pradesh and is currently being used internationally in Peru and Timor-Leste. The overall framework of the Swasthya Slate operations involves diagnostic devices interfaced to a Bluetooth unit. An affordable diagnostic device has been taken and readings have been digitized. These digitized values are sent to an Android tablet, wirelessly. In the tablet, a free-to-use application called Swasthya Slate allows the healthcare worker to take demographic details as well as the clinical information of the patient. (https://www.phfi.org/our-activities/affordable-health-technologies).

Covering a wide range of products, from simple bandages to the most sophisticated life-support products, the medical devices sector plays a crucial role in the diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, and treatment of diseases and the improvement of the quality of life of people suffering from disabilities.

Over 70% of India’s population lives in a rural setting. Hence, it goes without saying that providing adequate health care to this group is of paramount importance. In order for that, we need an improved and reorganised healthcare delivery system. The delivery system tasks include motivating women to give birth in hospitals, bringing children to immunization clinics, encouraging family planning (e.g. surgical sterilization), treating basic illness and injury with first aid, keeping demographic records, and improving village sanitation. But their most important contribution is to serve as a key communication mechanism between the healthcare system and rural populations.

Mobile phone ownership in India is growing rapidly, six million new mobile subscriptions are added each month and one in five Indian’s will own a phone by the end of 2007. By the end of 2008, three-quarters of India’s population will be covered by a mobile network. Many of these new “mobile citizens” live in poorer and more rural areas with scarce infrastructure and facilities, high illiteracy levels, low PC and internet penetration. Primary Health Care Services using Mobile Devices ensures improved access to primary health care and its gate-keeping function leads to less hospitalisation, and less chance of patients being subjected to inappropriate health interventions.

Amongst the many ICT options available to govt to improve the efficiency& effectiveness of its delivery process of primary health care, mobile & wireless technologies offer some exciting opportunities for a low cost, high reach service. There is strong evidence that mobile technologies could be instrumental in addressing slow response rates of govt to citizen requests, poor access to services, particularly for low-income and marginalised populations in underserviced rural areas. The use of mobile devices by health care professionals (HCPs) has transformed many aspects of clinical practice.

Hardik Panchal was a student of e-learning course in Public Health Management(ePHM) conducted by Institute of Public Health, Bangalore, India.

Disclaimer: IPH blogs provide a platform for ePHM students to share their reflections on different public health topics. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and not necessarily represent the views of IPH.

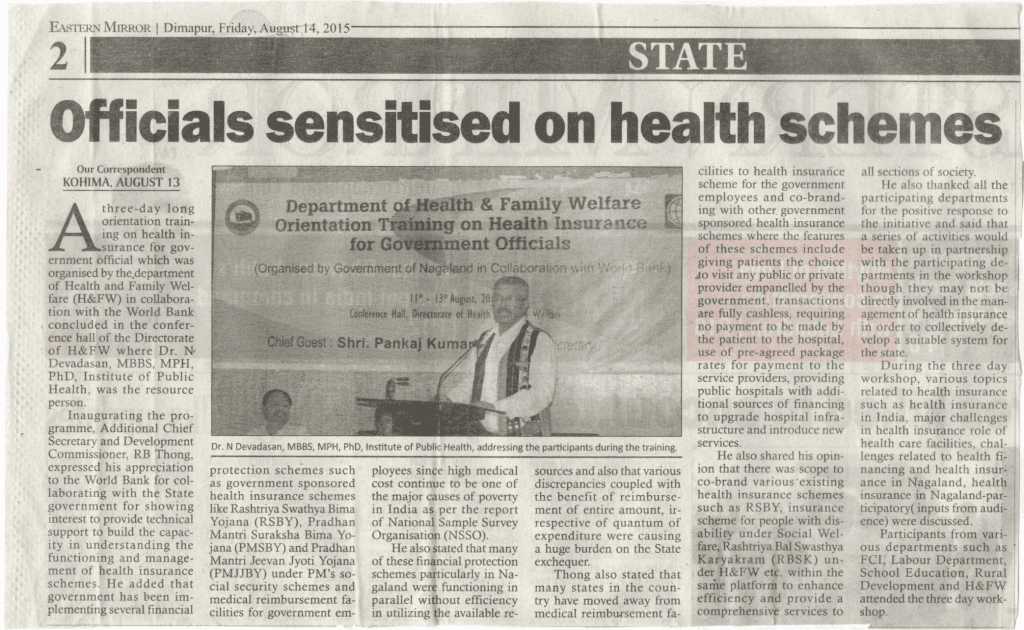

by iphindia | Aug 20, 2015 | Blog, Education, Latest Updates, Media advocacy

by iphindia | Aug 13, 2015 | Blog, ePHM-Advance, Latest Updates, Short Course

As we all know and recognise that community health workers (CHW) are the part of the community and have a significant role to play for our health improvement. There is plenty of scientific evidence wherein community involvement has increased the reach and impact of health systems. This works for communicable and non-communicable disease programmes as well as health promotion and prevention (TB, malaria and HIV care and prevention). I strongly believe that the success of pulse-Polio programme, was immensely contributed to CHW and similarly we could say that the TB-DOT programme has its success attributed to CHW. It has become clear that their support have unique advantages including their closeness with the community, their ability to communicate through people’s own culture and language and also to understand the needs of the communities and their ability to mobilize the community members.

Based on my experience with the CHW, I feel following are some of the objectives for their involvement into any programme:

1. They have acces s to the target community, as they are from the community and have acceptability within the community.

s to the target community, as they are from the community and have acceptability within the community.

2. Bridges the gap between the community and programme

3. Increases outreach for the programme

4. Community empowerment

5. Prompt response for any emergency need of the community

6. Facilitate improvement in surveillance and monitoring of any programme.

7. Facilitates in community mobilization for any activity.

Our government has acknowledged their contribution to the improvement of health status. I could easy quote an example from India, like ASHA (Accredited Social Health Associate) are local volunteers who are recruited through panchayat system and Village Health Committee

Under National Health Mission Programme (NRHM) with specific selection criteria. Following their recruitment, they are imparted training on regular basis for various programmes. For eg. in malaria programme, they are responsible for mobilizing community to accept the Indoor Residual Spray (IRS) and Long Lasting Insecticide Nets (LLINs) and also how to diagnose the case by using Rapid Diagnostic Treatment (RDT) kit, preparation of blood smear/slide for further investigation etc. They are also involved in collecting data from the villages for further assessment by the programme managers. Their performance is assessed from time to time by the state/district team and accordingly they are paid their incentives.

However, I have experienced that it was difficult to sustain them for a longer duration and we came across the following few challenges in the programme:

● Lack of supportive supervision and motivational activities.

● Overloaded with activities of multiple programmes;

● Logistic and supply management for various programmes;

● Acceptance by the community;

● Dependency of community on volunteers;

● Timely payment of performance linked incentive through single window system;

We felt that these challenges be addressed jointly by the community and the government authorities to sustain them for the benefit of the programme. Few suggestions include; a CHW should be assigned to manageable number of households instead of villages to avoid overburden of work; to provide integrated training; community could also contribute in supporting CHW through motivational programmes including honouring them and acknowledging their work from time-to-time. Having said this, we still cannot see a programme without their involvement and it would not be out of place to mention that the success of any health programme primarily depends on the these community volunteer.

Jatinder Chhatwal was a student of e-learning course in Public Health Management(ePHM) conducted by Institute of Public Health, Bangalore, India.

Disclaimer: IPH blogs provide a platform for ePHM students to share their reflections on different public health topics. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and not necessarily represent the views of IPH.

by iphindia | Aug 12, 2015 | Blog, ePHM-Advance, Latest Updates, Short Course

Health has long been defined as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity ’. This clearly implies the need for promoting ‘holistic’ well-being and comprehensive healthcare that enables people to increase control over improving their own health. This process entails raising health awareness, enabling informed choice, disease prevention and control. Action in health promotion requires that efforts move beyond the boundaries of an absolute biomedical approach, towards one that takes into account the wider determinants of health including social, economic, political, cultural and ecological factors.

Incorporating health promotion mechanisms at every level of our health system is essential. In this blog, I share a few reflections derived from my experiences with health promotion and disease control activity.

Incorporating health promotion mechanisms at every level of our health system is essential. In this blog, I share a few reflections derived from my experiences with health promotion and disease control activity.

HEALTH PROMOTION AND DISEASE CONTROL

I have in the past, had the opportunity to closely observe and be a part of health promotion programmes dealing with cancer awareness, prevention and care. While I had the opportunity to work within the Cancer Screening Programmes in the UK, it was clear that the programmes had been carefully designed, strategized, piloted and rolled out in an evidence-based manner. Understanding the disease, its anatomical symptoms and more so its aetiology at a molecular level, and the social factors influencing its development, held centre focus in the design and implementation of the population-wide disease control programmes. In Bangalore, I had the opportunity to set up a hospital-based cancer registry programme as part of the wider national programme. Being hospital- based, it was the first time that the ‘patient’ was brought into focus in my work with cancer, and in the process; the seriousness, complexity and reality of the disease with its wider issues governing all aspects of disease awareness, prevention or cure became more apparent and significant.

Simultaneously, my background in Immunology began to re-iterate the significant role our human immune system plays in linking the impacts of our environment with our health outcomes. The Government of India has made efforts to incorporate health promotion into the health system through various intervention-based disease control programmes. Such programmes are important in the short term; however their predominant vertical, biomedical (drug-based) approach is futile for sustained disease control. They fail to consider the wider social determinants of health (SDH) that govern individual and population immunity. One such vertical intervention is the DOTS–TB Control.

Programme introduced under the NRHM.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains a major national and global health problem and is no longer only a disease of the poor; but rather a disease of compromised immunity. Various factors like financial poverty, undernourishment, small, overcrowded and unhygienic living conditions, lack of health awareness and poor health / medical practices; all culminate, to directly or indirectly impact on human immunity and influence susceptibility to TB. The evolution of multidrug-resistant TB strains greatly challenges the efficacy of anti-TB drugs. Furthermore, Directly Observed Treatment, Short Course (DOTS) despite its advantages, fails to address the basic principles of autonomy, appropriateness, accessibility and acceptability; essential for successful adherence and compliance to such a disease control strategy. Responsibility to one’s own health and the sense of personal agency is crucial in positively influencing the SDH and thereby health outcomes.

Recent media campaigns promote the importance of TB diagnosis and uninterrupted treatment via the DOTS programme. While this is a powerful effort in health promotion, it fails to convey the very significance of nutrition and a healthy immunity in TB prevention and control.

HEALTH PROMOTION AND THE INDIAN HEALTH SYSTEM

Health promotion is complex and requires adequate reflection, effort and resources. We are fortunate as a country to have the aptitude and the means to build a massive and effective health promotion campaign as a part of our existing public health system. A successful example of disease control through health promotion activities (education and prevention strategies) and multi-sectoral efforts (including The Ministry of Rural Development, Govt. of India, State Public Health Engineering Departments, and the Rajiv Gandhi National Drinking Water Mission (Rural Water Supply) in India; is the Guinea Worm Eradication Programme. Health promotion has the potential to move beyond the NRHM’s vertical interventions through cross sectoral engagement (sectors that influence the daily lives of the public and their health). Addressing the SDH through such an approach would ensure that important disease–contributing factors like micronutrient deficiencies are addressed even via the food industry, for example.

Health protection through immunity building and addressing the SDH from within the Public Health system and across sectors, to introduce well-planned horizontal efforts together with vertical interventions is a way forward.

Janelle de Sa was a student of e-learning course in Public Health Management(ePHM ) conducted by Institute of Public Health, Bangalore, India.

Disclaimer: IPH blogs provide a platform for e-PHM students to share their reflections on different public health topics. The views expressed here are solely those of the authors and not necessarily represent the views of IPH.

India with a current population of 1.25 billion is posed to be the highest populated country with 1.6 billion by 2050. Indian public health planners have a huge challenge ahead – to serve and keep population healthy. Health care service resources will not increase in proportion to this population increase. The situation of high geographical disparities in health and wellbeing of population in addition to the demographic and epidemiological transitions taking place during this period will demand continuous spatiotemporal adjustments in plans and realignment of health care resources allocation. To address these challenges, health-planning process needs to evolve by provisioning maximum use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in health care delivery and public health decision making at every level. This is to deliver right health services to right people at right place and on right time.

India with a current population of 1.25 billion is posed to be the highest populated country with 1.6 billion by 2050. Indian public health planners have a huge challenge ahead – to serve and keep population healthy. Health care service resources will not increase in proportion to this population increase. The situation of high geographical disparities in health and wellbeing of population in addition to the demographic and epidemiological transitions taking place during this period will demand continuous spatiotemporal adjustments in plans and realignment of health care resources allocation. To address these challenges, health-planning process needs to evolve by provisioning maximum use of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in health care delivery and public health decision making at every level. This is to deliver right health services to right people at right place and on right time.

s to the target community, as they are from the community and have acceptability within the community.

s to the target community, as they are from the community and have acceptability within the community.

Incorporating health promotion mechanisms at every level of our health system is essential. In this blog, I share a few reflections derived from my experiences with health promotion and disease control activity.

Incorporating health promotion mechanisms at every level of our health system is essential. In this blog, I share a few reflections derived from my experiences with health promotion and disease control activity.